You never forget your first IAAPA. Between the thousands of flashing lights, the mixture of Dippin’ Dots and fog juice wafting through the air, and the slow building sensation that this must be what war is like — it can be a lot. I first attended IAAPA over half a decade ago and that experience, while memorable, I can’t say was exactly positive. It was overwhelming, confusing, and surprisingly lonely. I left unsure if I even belonged in this industry. That experience could not stand in more contrast to my most recent IAAPA experience in November, in no small part thanks to the stellar work of the Big Break Foundation.

The Big Break Foundation was founded a couple years ago, at the height of the global pandemic, by themed entertainment industry veterans Chuck Fawcett and Patrick Kling. Run by executive director Monai Rooney, the organization seeks to improve inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility throughout the location-based industry. But from where I stand what the organization really excels at is relational experience design. It looks at the entire industry from above, and in a truly innovative way focuses on both the guest experience and that of the behind-the-scenes talent and identifies ways to improve the experience for everyone, regardless of where they exist in the system.

The Edutainment program is a perfect case study of this approach. I, along with 49 other students and recent graduates, from writers to mechanical engineers, from college sophomores to mid-career transitioners, and people from all over the country and world found ourselves on a whirlwind immersion program into the attractions industry. All of us had stories of barriers that we kept encountering: lost internship opportunities due to the pandemic that we were no longer eligible for, convoluted international visa requirements and companies unwilling to deal with them, possessing odd combinations of skillsets, unsure how to communicate our value. And over the course of the week I glimpsed a shocking amount of opportunities begin to unfold and the edges of some of the barriers begin to be sanded off.

Throughout most of the history of the themed entertainment industry, making your way in it has been rather difficult. It’s a career that people fall into through luck or who otherwise have had to navigate a dark maze of unmarked doors through sometimes dubious means. It’s often been a hostile climate: people forced to trudge forward for long hours in pain and discomfort with no map, not sure of where they’re going, where only the most obsessively driven, competitive, and frankly, privileged succeed. In short, it’s a place where most of the effort of experience design has been placed on the product, not on the halls where it’s created. But it doesn’t have to be that way and a new generation is looking to change that. Most pros that have been in the themed entertainment industry a while accept that the better the guest experience is the more money there is to be made. People want to be in places that are great to be in. What the Big Break Foundation recognizes is that axiom holds just as true behind the scenes.

The core of the Edutainment Program is a partnership with IAAPA that provides admission to the IAAPA Expo, EDUSessions, and a 1-year Young Professional IAAPA membership for free, to each of the 50 participants. That alone is huge. Tickets to the Expo are not cheap and the learning and networking opportunities contained within are invaluable. But Big Break goes way beyond basic access and curates an entire weeklong experience, a crucial component of which is community. A newcomer’s first exposure to this industry can often be formidable and isolating. As program participant and industrial designer Gabriel Nunez explains, “At times I felt out of place…a sense of alienation crushed me. How could I join the industry when I come from middle-of-nowhere, Costa Rica?…I found comfort in the rest of the Edutainment Pass Program participants…Thanks to all of them, I ended up feeling like I do belong, we all belong, no matter where we come from.” The Edutainment program combats the isolation of being new by curating a community before the expo begins, with online discussions and multiple meetings, so even on Day 1 you feel just a little less alone.

Once the expo does start, the program, this year run by the incomparable production manager Sara Needham and sponsored by B Morrow Productions, offers a treasure-trove of experiences that unlock IAAPA in ways 2016 me could never have imagined: Tours of the show floor from industry veterans happy to answer any question you can dream up. Nearly a dozen intimate discussions from even more industry experts happy to share their wisdom and chat one-on-one to answer questions. Schedules and directions to all the mixers and meetups you might not have even known were happening or existed. An invite to the Valtech party. And above all a community to do it with.

One aspect I love about Big Break’s approach is its individualized, generous spirit. A spirit that flows directly from their focus on IDEA principles. Take for example Sara’s story. They were a participant in the program last year and because of it were able to land an internship with one their top choice companies, but alas there have been additional barriers.

“Being a international graduate student has meant finding full-time employment comes with the added requirement of visa sponsorship…this extra requirement has made my own personal search very difficult. After my internship ended I reached out to Monai and Big Break Foundation to see if there was any way I could volunteer my time while looking for my next opportunity…Big Break gave me a focus, a chance to build some new skills…I became the point of contact for these students [and 33 industry professionals who spoke to them], building an exclusive Edutainment Program schedule for their IAAPA week…sourcing and scheduling chats…organizing booth volunteers…even speaking to the media on behalf of Big Break Foundation. In a time where I couldn’t find my next step and wanted to give up, Big Break Foundation put me in a position to keep moving forward and serve my community.”

This generous, individualized spirit extends to everyone the foundation encounters. The Edutainment program regularly invites people it meets on the floor to relevant events and encourages participants to do the same, when the circumstances allow, because they recognize the goal is creating a better experience for everyone — lifting everyone up. The trailblazer chats were formed through requests of the participants, of people we directly asked to hear from. And Monai and Sara both make it a point to get to know every participant by name, learn what they want to do, and try to connect them with the people that can make it happen: an attitude quickly mirrored by all the attendees.

Of course the Big Break Foundation knows that there are so many more people out there that could use a hand than the 50 they’re currently able to sponsor. In fact, the Edutainment program is only a small portion of the work they do throughout the industry to try to create a welcoming experience for everyone. This is where their relational experience design expertise comes in. The Big Break Foundation goes beyond quick fixes, and even beyond the model of guest service, to the very core of how experiences are created: how we relate to each other, our environments, and the structures we operate within. Through the principles of Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility, the Big Break Foundation seeks to transform the guest and employee experience alike into something better for all.

I don’t think a lot of people recognize the mental toll being a newcomer, being marginalized, or just having rotten luck can take on a person trying to make their way. Nunez talks a bit about this, “I applied because not many believed in my dreams of becoming a ride designer when I was kid. I applied to show there’s people outside the US with ambition and talent willing to give it their all to become part of this industry. I applied so that one day another student with similar aspirations can look back and see that our voices can be just as strong as anybody else’s. That no matter the barriers that being queer Latinos pose, we will make it.” Many of us in the program have dealt with the lack of confidence being on the outside can bring. I feel echoes of Gabriel’s journey in my own story. One of the reasons I’m pursuing a career in themed entertainment now and not 15 years ago is because as a closeted trans teen I was bullied for loving theme parks, faced with homophobic derision about it, and didn’t have the confidence to say “this is what I want.” Much like Gabriel I hope that my presence now might help some other person who feels afraid to go after what they want. IDEA principles and the relational experience design expertise Big Break provides help cultivate an atmosphere where people like us can feel we belong.

People often get scared or defensive when the IDEA words pop up. Such big aspirations must mean a big change. Change is scary. And sure there is no denying there’s a lot to work on. But really it’s just about helping people: about being kind, generous, welcoming, and curious. It’s about being as intentional in crafting the experiences between each other as we are in creating the ones made out of concrete and steel. To make room for everyone, as the monorail announcement goes.

All week I heard story after story about the opportunities this approach was able to unlock for my peers. Wren Sullivan, another participant and concept artist puts it well, “Applying for Big Break Foundation is one of the most beneficial things I’ve done. All of their fireside chats with industry professionals really gave me the opportunity to understand the industry more, network on a closer basis, and reconfirm that this is the industry for me…I was overwhelmed by the amount of networking that happened amongst all of the Big Break Foundation scholarship receivers.” Matthew Curnutte, participant and mechanical engineer echoes the sentiment, “I’m so glad I got selected. I got way more out of IAAPA Expo through Big Break Foundation than I would have going on my own. “

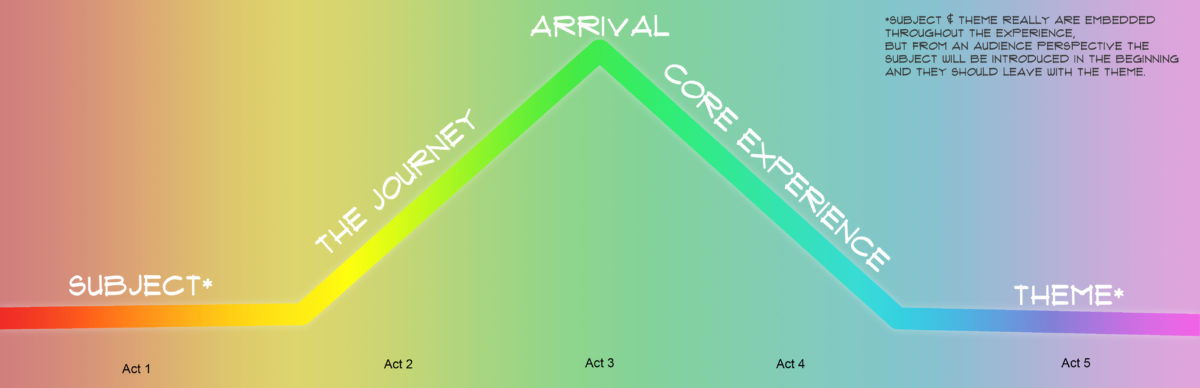

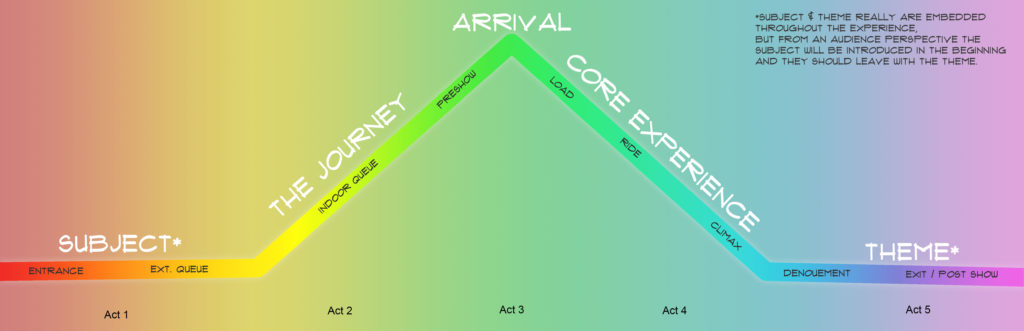

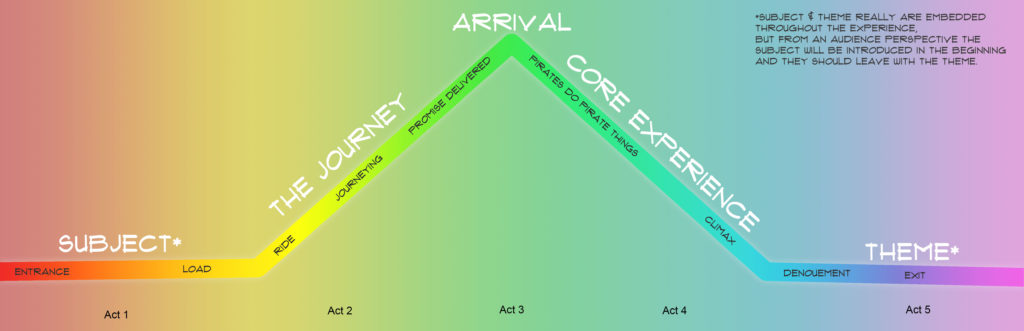

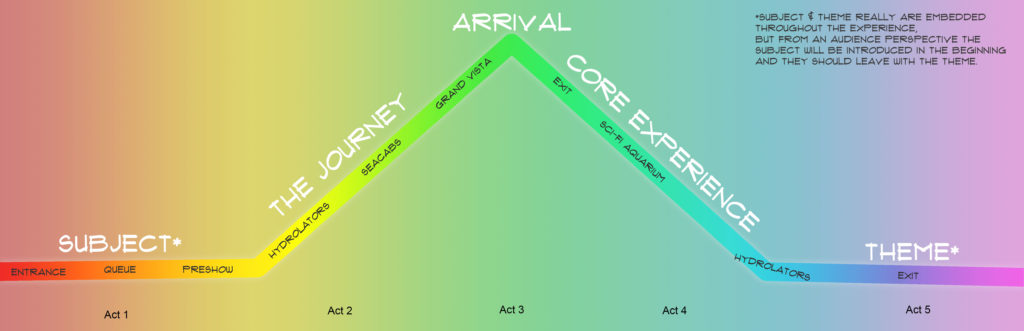

Big Break asks, “what if we paid as much attention to the experience between each other as we did to the one in Revit?” What if there were people around every corner looking to make your journey just a tad more easy and pleasant, one where you’re given a map and aren’t stuck in line, so that you can save your energy for the actual job. Big Break gives new tools to improve the guest experience in ways that have been historically overlooked and for the first time applies the techniques of great experience design to behind the scenes creators, operators, and those that aspire to become them. It does this by being holistic, by not focusing on one individual detail or demographic, but by focusing on how all the elements work together, just as the best experience designers do, to make a seamless experience for everyone. I feel so grateful to have gotten to be a part of their Edutainment program this year, and so excited by the energy I witnessed among my fellow participants. There’s so much fantastic talent on the horizon and Big Break Foundation is making all of our journeys a better experience.