This has been something I’ve been thinking about for a while. It seems to me that some problems the themed entertainment industry is facing today could be solved by looking at the way things were done in the past.

For example, a problem that has always plagued theme parks from the beginning is queueing. No one likes it. And yet as parks get more and more popular, the queues grow with them. The problem has been exacerbated over time as the trend in experiences has been for rides to grow increasingly more intimate and ever shorter in duration. The thing is, problems of capacity have been addressed before in the past. Innovations at the 1939 and 64 World’s fairs were instrumental in developing ride systems built to handle enormous crowds. The Omnimover, the flume of boats, the traveling theater, the peoplemover, the carousel theater, even the parking lot tram all trace their roots to these events along with many others. A real priority was placed on moving people as efficiently and with as great a number as possible: On giving a great experience, including the experience of not wasting most of your day waiting for absurd lengths of time in line. Perhaps this was because people were paying for attractions individually, but it was a damn good lesson to learn.

This people-moving philosophy was taken back to Disneyland – new attractions like Pirates of the Caribbean and the Haunted Mansion / Inner Space along with the World’s Fair imports moved people in numbers that hadn’t been seen at Disneyland before: multiple thousands per hour. And this philosophy migrated to Florida as well where everything was bigger in 1971 with THRC’s at a minimum of 2000 people an hour for most attractions. And Disney went even bigger again when they built Epcot. A park truly built for massive crowds – where nearly every major ride was a people-swallowing next-gen omnimover. These were attractions that were built to minimize waiting on one hand and to hold on to crowds for long periods of time on the other: pavilions designed that could easily hold guests for multiple hours, rides that might hold on to them for almost as long. World of Motion had a mind-shattering capacity of over 3200 people per hour, a ride length of 15 minutes, and a post show that could take someone a good half hour to walk through.

The designers of Epcot knew how important it was to keep lines moving, to keep them as short as possible, to keep as many people off the streets as possible and inside attractions, restaurants, etc. The larger the ratio of experience time to queue time the better the perceived value becomes, the lower the perceived wait becomes. The less crowded people feel, the more relaxed and happier they feel – more likely to spend more time and more money. This approach continued until the end of the 1980s at Walt Disney World – the last major people eaters probably being The Great Movie Ride and Backlot Tour but the approach continued and was expanded a few miles north at a new competitor.

If Disney was the first to embrace handling large crowds, Universal was the one to really take it in a new direction. Up until that point Disney had mainly addressed the problem by building omnimover and theater after theater after omnimover – but Universal thought of some clever additions to fit their own story style – approaches that I find quite precient given the state of things today.

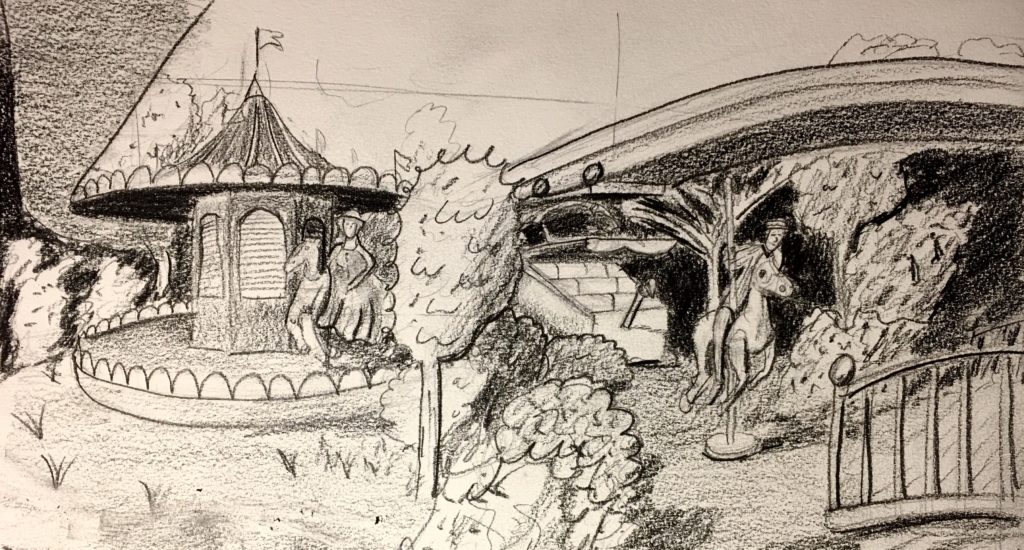

Universal’s story style has never been passive. While Disney attractions largely have their roots in guests playing a passive bystander or fly on the wall, Universal has always been about thrusting you into the middle of the action: A strategy that doesn’t work terribly well with the features of the traditional ominmover or a theater. Universal instead experimented with ride vehicles that were both agile and large. Perhaps because of the inspiration of their tram tour, rides like Jaws, Earthquake, and Kong sat massive amounts of people within a single vehicle and yet managed to move within detailed and expansive sets in ways that added to the story and still felt intimate. Maybe this has to do with the outsize action common to their early attractions – making the massive vehicles seem miniscule by comparison.

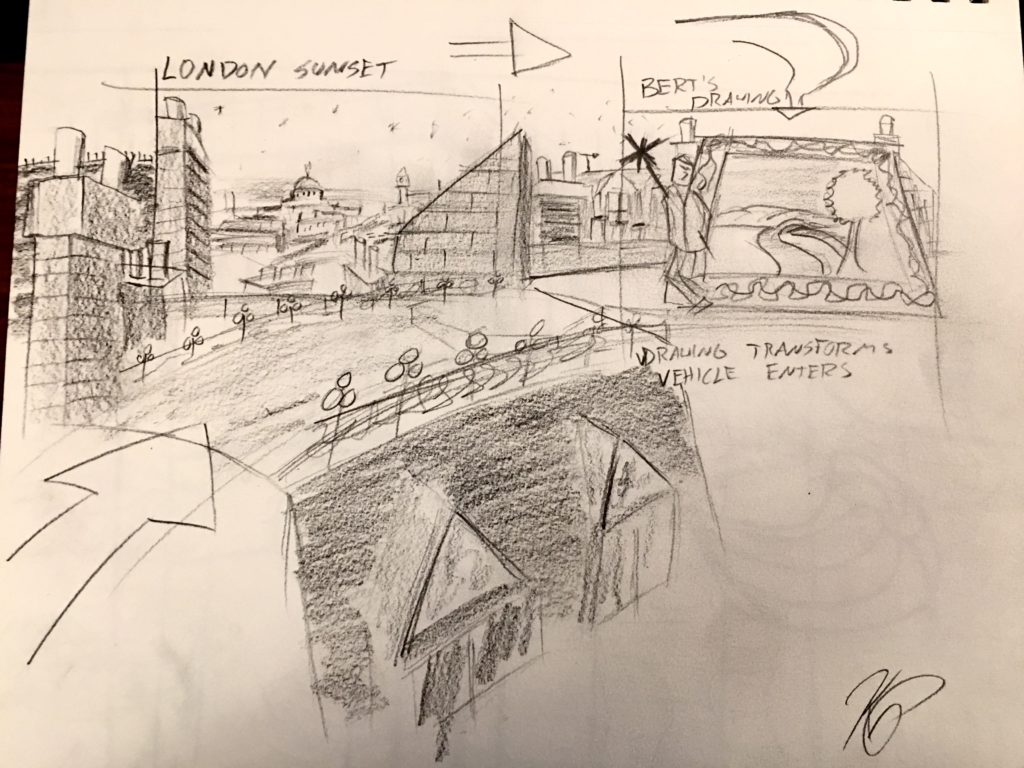

Another technique that I truly think was brilliant and so far ahead of its time was seen with Earthquake and later Disaster! and also to a lesser extent E.T. These are the first attractions I’m aware of that really sought to integrate the majority of the queueing process into the overall experience – turning a relatively short ride into a much longer attraction. Earthquake by far did this best, and in a way that has still really yet to be seen again, though I’d predict is the key to solving the queueing problem once and for all in the future. Earthquake turned the queue into a multi-stage show. After waiting for a few minutes outside guests were brought inside to see several effects demonstrations, a recorded presentation, participate in a full mock filming of a scene, and only after all of that were shown to their vehicle. It was a Universe of Energy approach where instead of the theaters moving, the guests did. All the elements of what were presented tied together with the final climatic ride. While essentially just multiple elaborate pre shows the effect was to create an attraction with a length closer to 30 minutes and a line of 15 rather than what it really was: a line of 40 minutes and a ride of 5.

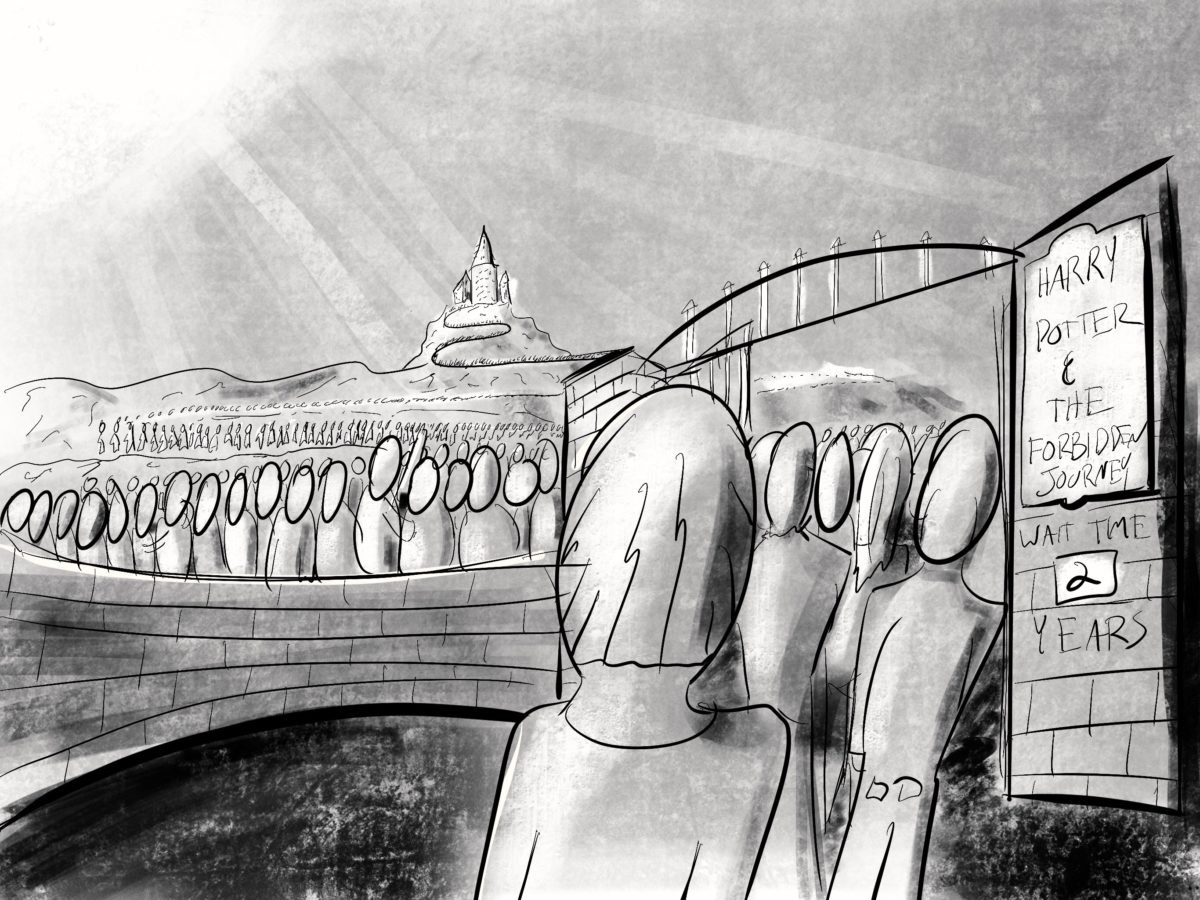

And then sometime in the 90s it seems moving guests quickly, efficiently, and with as little perceived waiting as possible somehow lost its priority. New technologies ushered in an ability to specifically time and craft rides that operated on very intimate levels. Attractions got both shorter and handled fewer people. The 12 person vehicle became popular, then the 6, then the 4. At the same time theme parks got more popular. In the midst of all this the idea was struck that technology could eliminate the queuing problem once and for all. Systems like Fastpass and Universal Express were introduced that in theory would redistribute crowds and make use of underutilized capacity (and push guests into stores and restaurants). In reality, they’ve served to increase the waits of nearly all attractions and overcrowd stores, restaurants, and paths. What’s worse: parks are pursuing these strategies full steam ahead with Universal debuting it’s Tapu bands and virtual queueing for all attractions. This is a mistake unless a fundamental rethink of how a park is designed occurs. Where exactly are the all the people who are not waiting in line going to go? What are they going to do? Only so many meals can be eaten and gift shops visited. Thousands of extra people are now walking the paths of your park with nothing to do – bored and making the park seem infinitely more crowded than it needs to seem. And while attendance is at all time highs, new E-ticket attractions are routinely built with THRCs less than that of opening day attractions in 1971. Less than that of attractions built in the 1960s. The 2 and 3 hour wait have become expected standards to work off in the design phase – with attractions like Flight of Passage being specifically designed to accommodate that many people or more within their queue walls.

Flight of Passage has a terrific queue, possibly the best queue ever designed, but yet I can’t help but feel that it’s kind of solving the wrong problem. We shouldn’t be solving how to accommodate three hours worth of standing, grumpy, sweaty tourists in a way that they’ll still feel like riding an attraction at the end and not self-immolating. The problem should be solving how to ensure guests aren’t standing in a line for 3 hours. It’s ridiculous that we’ve reached a point where the building of one of the largest and longest dark rides ever built (Universe of Energy: THRC 2432, 45 minutes long) – a dramatic people eater, is only big enough to hold the queue for what is rumored to be a 3 minute ride.

How are guests supposed to have a great experience when they’re spending most of their day standing in lines? How are guests supposed to have a relaxing vacation or day out when all their time is spent worrying about meeting their schedule, assigned times, darting back and forth, and whether they’ll be able to do everything on their list and whether they can ever afford to come back? As experience designers, the job is not only to design the amazing experiences within an attraction or park, but it should also be to design the experiences guests have throughout their visit. A trip to a theme park should be relaxing, energizing, an escape from the over-scheduled hustle and bustle and nickel and diming of the real world – a better alternative, not a microcosm.

The whole thesis of this article is that we can look to the past to find ways to help address this problem now. So what solutions can we find? First, capacity targets of attractions have to be increased. It cannot be acceptable for attractions at the most visited parks on earth to handle less than 2000 people an hour . Every effort should be undertaken to find and develop ride systems that can handle 3000 and approach 4000. While these systems may not be practical in all use cases – one has to think they would work in at least some. The pursuit alone would be beneficial. More important than individual capacity is collective capacity – how many total things there are to do in the park and how high each of their capacities are. It wasn’t just that the attractions of opening day Epcot had high capacities, it was that there were many attractions that all had those capacities and could hang on to those people for a long period of time.

Second, find ways to integrate the necessary queuing fully into the experience. Queuing surpassed the days of the simple switchback to the nicely decorated labyrinth long ago and now it needs to graduate from that. Queues must become an integral part of the show. An Act One or Two. This can take creative forms, a queue no longer has to be people standing in line. It can be a room with activities, it can have live entertainment, it can be a show, it can be a form of high-capacity ride. To their credit designers are exploring some of these options now with attractions like Gringotts and some upcoming rides at Disney but it needs to be taken to the extreme. If three hour waits aren’t going anywhere anytime soon, then we need to be creating experiences that fill at least one of those hours.

Finally, I’d say beware of purely technological fixes to problems. Shuffling guests around can alleviate stress around the edges but it will not be the answer. The people are still there.

This is just one of the many ways that looking to the past of themed entertainment design can help us when looking towards the future. There’s a wealth of novel solutions to problems that are just sitting there forgotten or overlooked. Older modes and styles of design and story could potentially show a way to tame ever-increasing budgets, ways of stocking merchandise and approaches to revenue generation may lead the way to increasing guests sense of value. There’s a wealth of strategies that are just sitting there, that while maybe most have outlived their prime (perhaps precooking all food in a central kitchen days in advance wasn’t a good plan), just a few could save the day.