This might not be my most eloquently prosed post, the final stretch of grad school is upon me and time is at a premium, but I have thoughts I want to share.

So I’ve been doing a lot of thinking into how to develop impactful and fun stories and attractions and I’ve think I’ve narrowed it down to 4 elements, from which the entire experience evolves.

The first two are often talked about by Joe Rohde. First you have,

- Theme: the moral of the story or message of the storyteller.

- Subject: the “actors” that illustrate the story. Not only characters, but also place.

Then there’s two more I’d like to add.

- Experience: this is the core event you will witness or participate in. Only a few words. Think archetypes. This is similar to the aspirational quality that some theme park designers have talked about, but more importantly it is the lens through which the entire story will be framed.

- Journey: the way we get there or specific premise. Think of it almost like a writing prompt. (Note: I debate whether journey belongs here because it’s somewhat determined by the other three)

You put the four together and the beginning of an attraction story begins to take place.

For example in Rise of the Resistance we can see that

- Theme: Good Vs. Evil. Evil will lose.

- Subject: Star Wars. Intergalactic Civilizations. Spaceships.

- Experience: Prison Break

- Journey: Recruited into a space army and captured.

Or The Haunted Mansion

- Theme: Death is actually kinda funny.

- Subject: A Haunted Mansion

- Experience: Guided Tour

- Journey: Deciding to visit that old creepy mansion

Of course there’s room for interpretation but with these four events you begin to see how any satisfying ride might be crafted. Even at random. Say you have.

- Theme: Be careful what you wish for

- Subject: Construction Equipment

- Experience: Flight

- Journey: stumble into an abandoned construction site at night.

One can start easily piecing together an attraction from this. Bob the Builder is tired of construction and wishes to do something more glamorous. We stumble upon him in a construction site right as he makes a wish for more excitement – causing the construction equipment to come alive. But it quickly grows dark as the construction equipment doesn’t like being unappreciated and chases us into the night sky on a whirlwind journey. Eventually it all comes to an end and Bob and us both realize that life is plenty exciting as is.

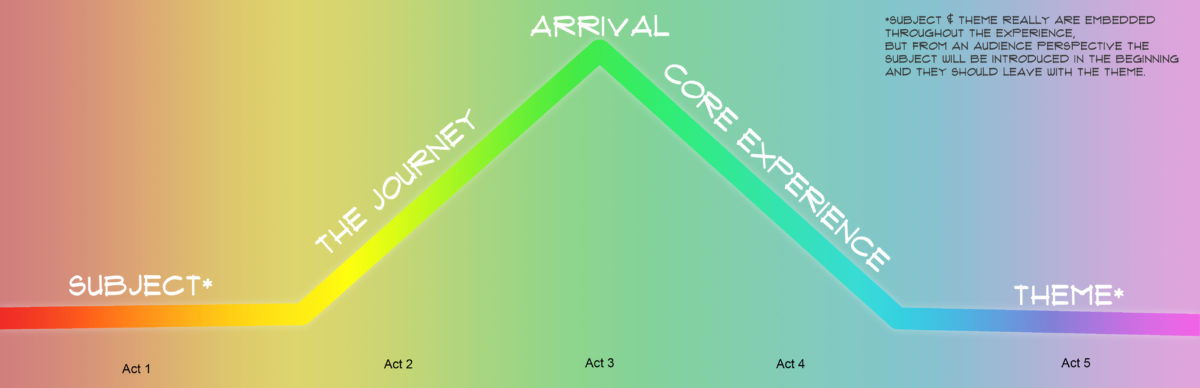

Where this framework gets really exciting is how it ties into narrative 5 act structure. You have your four pieces of framework. Now what? Well let’s look now at classic five act structure. You’ll remember it from English class. I’m no expert, but here’s my summary

- Act 1: Exposition: the world is introduced

- Act 2: Rising Action: the main character sets out on a journey

- Act 3: Arrival: the character achieves their initial goal. But at the midpoint of this act something happens which changes the equation and sets them on a new journey

- Act 4: Journey Home: character sets off on the final quest. The final confrontation occurs at the transition to act 5

- Act 5: Resolution and Denouement

The key thing to remember is that each key moment in the story occurs at an act transition, with the third act split in two – the key reversal occurring there. (All of what I’m about to say could be mapped onto 3 act structure too, but I think 5 makes it easier to talk about).

So anyway…you’re building a ride. What goes where? Well I’d propose that nearly all attractions follow a simple rule. The Journey is everything that happens before the midpoint and the Core Experience is nearly everything that comes after. The theme and subject are what color each scene within and determine the ultimate outcome.

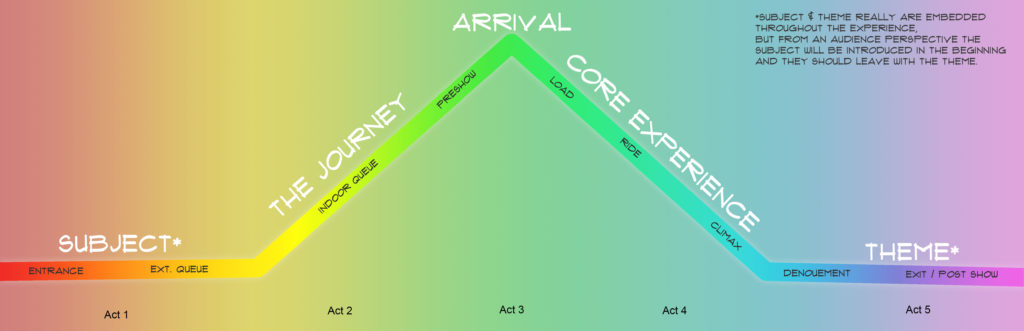

In modern attraction design it looks something like

- Act 1: Entrance and early queue. The setting and world are introduced.

- Act 2: Queue: the queue takes us on a journey into the world on our way to a promised experience (not always the core experience, but often). We learn about the world, and it’s rules, and why we’re there.

- Act 3 Part One: Preshow: We arrive at the promised destination and new information is revealed that will set us on a new quest.

- Act 3 Part Two: Load/secondary queue: The core experience (which follows its own three act structure) begins

- Act 4: The Ride: We live out the meat of the core experience which leads us to one final climatic moment.

- Act 5: Climax & Exit: We experience the climatic moment of the core experience, and the story quickly resolves itself as we exit the vehicle with a denouement then or shortly thereafter.

For example Indiana Jones and the temple of the forbidden eye:

- Act 1: We come across an archeological dig at a temple

- Act 2: We venture into the temple to see what’s up and learn this is a creepy place.

- Act 3 Part 1 : we come across Sala and he tells us about quest expeditions we’ve somehow signed up for and the legend of the forbidden eye. Also we need to find Indy.

- Act 3 Part 2: we decide to go on our own expedition (the core experience begins)

- Act 4: The expedition throws up many obstacles of increasing threat level, preventing us from rescuing Indy until

- Act 5: We nearly get crushed by a Boulder and narrowly escape. Indy lectures us since we were the ones that needed rescuing and we slowly make our way out of the scary temple.

Or Rise of the Resistance

- Act 1: We find the rebel base

- Act 2. We are tasked with a mission to space but something goes wrong

- Act 3 Part 1: We’re captured and thrown in prison

- Act 3 Part 2: We’re rescued and begin our prison break (core experience)

- Act 4: We journey through the prison facing increasing obstacles trying to make our way home until

- Act 5: a final climatic encounter and daring escape pod run. We’re told we did a good job and exit.

As long as queues are long, and rides are short I predict this is the specific way we’ll see the structure implemented. What’s interesting though is looking to the past to see how rides and attractions then still followed the same structure BUT implemented it differently.

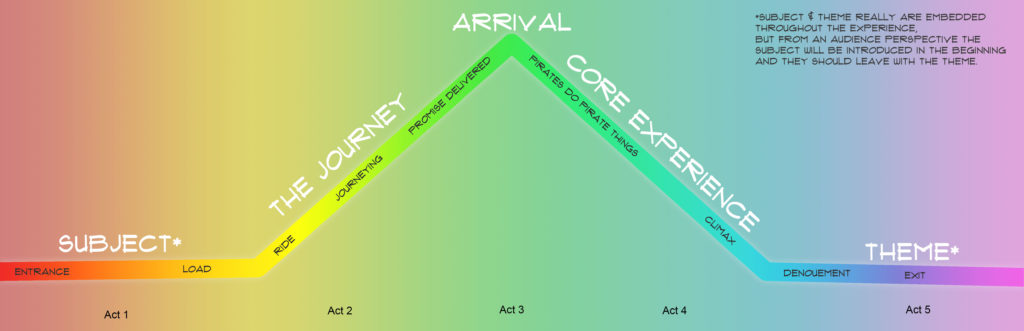

For example, before queues were really designed as part of the experience, it was common for the ride to begin as early as the beginning of Act 2. Let’s reference Pirates of the Caribbean (California version)

- Act 1: We are introduced to New Orleans square and the Blue Bayou.

- Act 2: We begin a journey through the bayou and enter mysterious caves

- Act 3 Part 1: We learn that pirates used to inhabit these caves

- Act 3 Part 2: The pirates materialize and the core experience of seeing pirates do pirate things begins

- Act 4: Pirates do pirate things until

- Act 5: The town climatically burns down, they all drunkenly kill themselves, and we exit this fever dream and end up back where we started.

Now consider how Pirates was adapted when it moved to Florida and it adopted the new-fangled immersive queue. The immersive queue replaced The Journey portion of the ride leaving only the Core Experience. The overall structure of the story was preserved, but what specific elements achieved it changed.

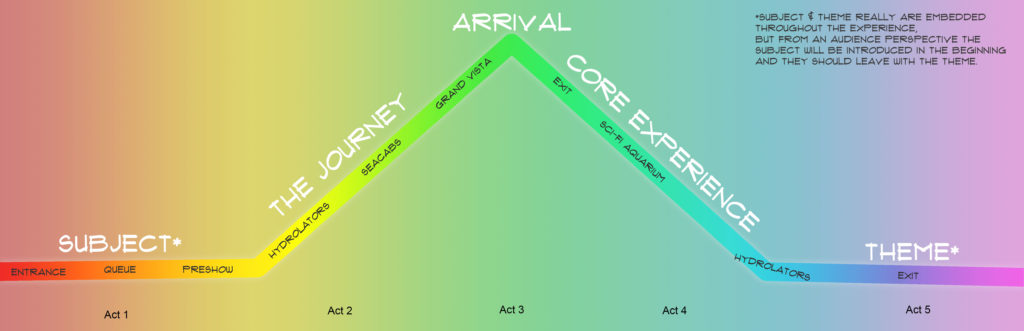

There’s even a ride that has a more unusual implementation. Let’s look at The Living Seas. For starters

- Theme: The ocean is majestic and cool

- Subject: Seabase Alpha

- Core Experience: Explore an Alien World (And/or aquarium)

- Journey: Specialized technology takes us deep under the sea

Now:

- Act 1: We’re introduced to the history of sea exploration in a museum and documentary

- Act 2: We begin our journey under the sea via Hydrolator

- Act 3 Part 1: We take sea cabs to further our journey

- Act 3 Part 2: We arrive at Seabase Alpha

- Act 4: We explore Seabase Alpha (core experience)

- Act 5: We leave Seabase Alpha via Hydrolator

This is the only attraction I’m aware of that has used the ride as a journey rather than the core experience. It’s an unusual implementation but it just goes to show that any means can be used to achieve any part of the structure, as long as all parts of the structure are there, you get yourself a satisfying experience.

The more I think on it, the more I think nearly all attractions can be conceptualized in this framework, and better yet this framework provides a nice blueprint to develop new attractions. Does it apply to your favorite?